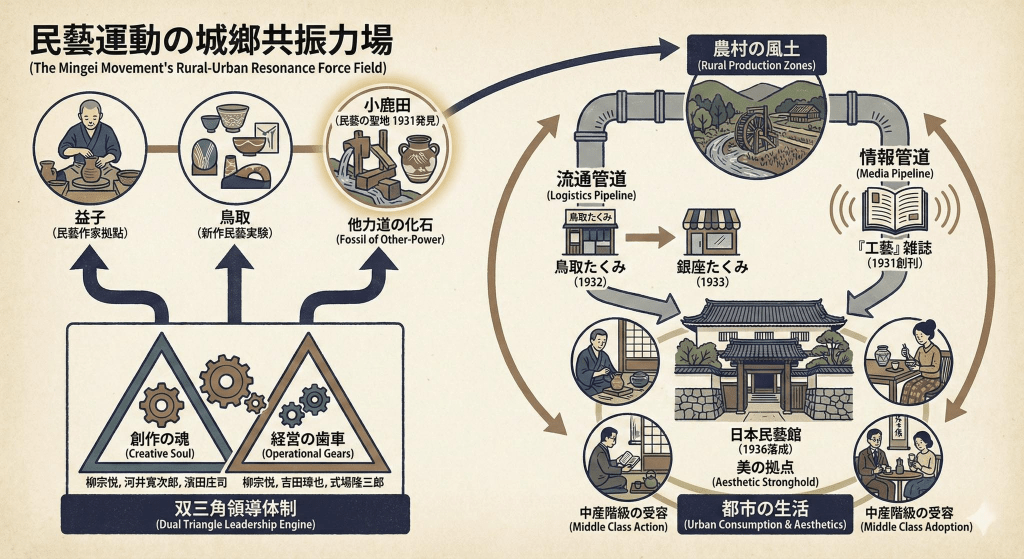

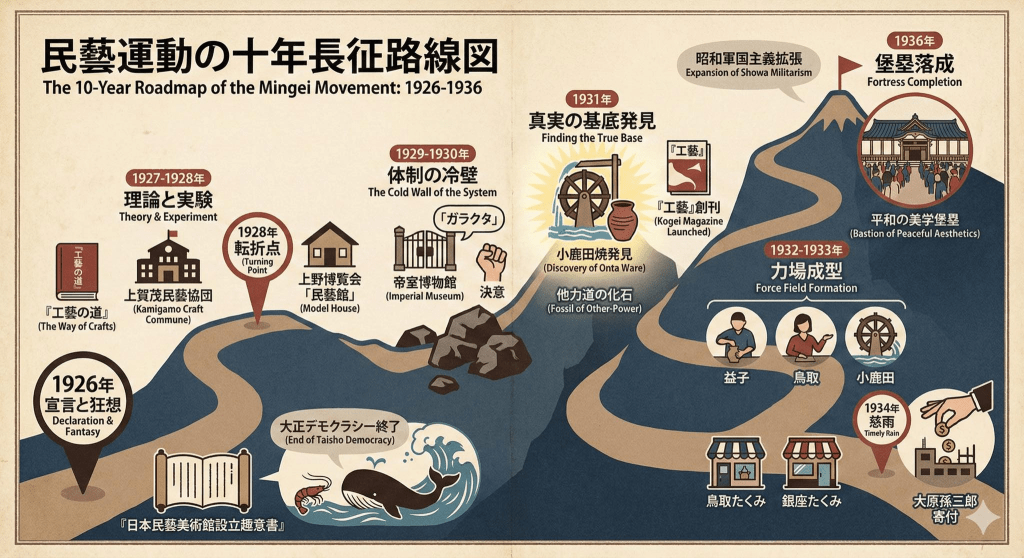

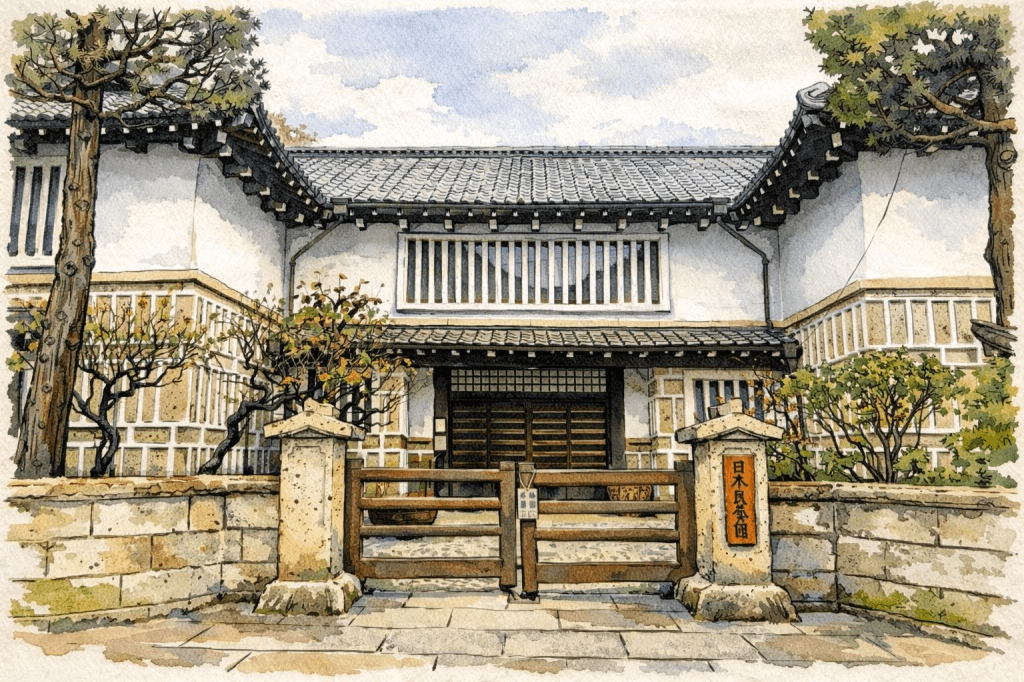

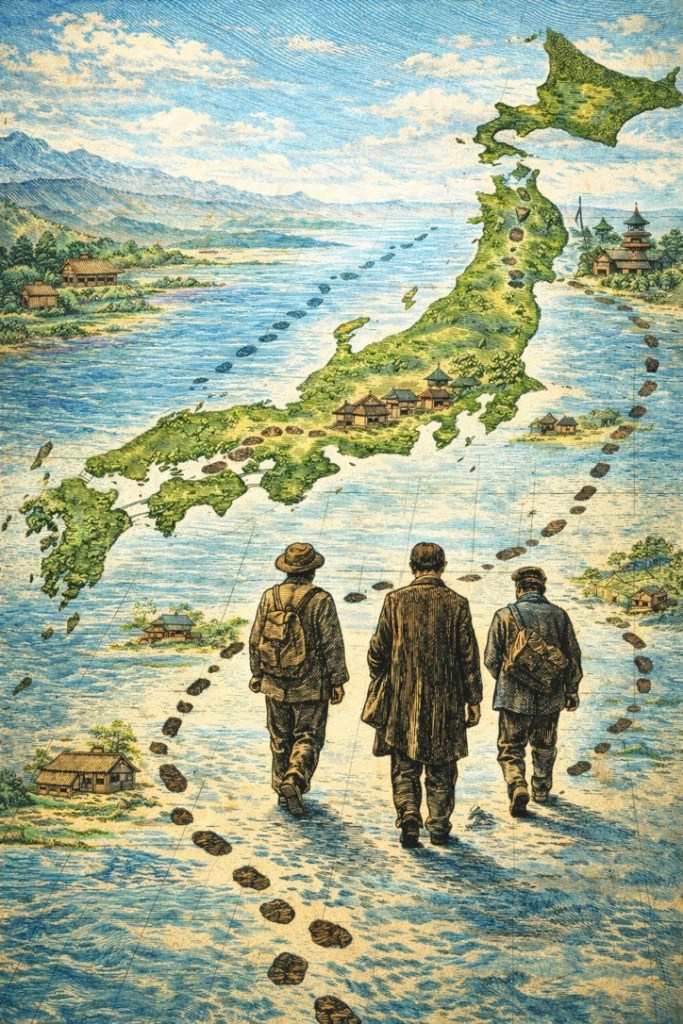

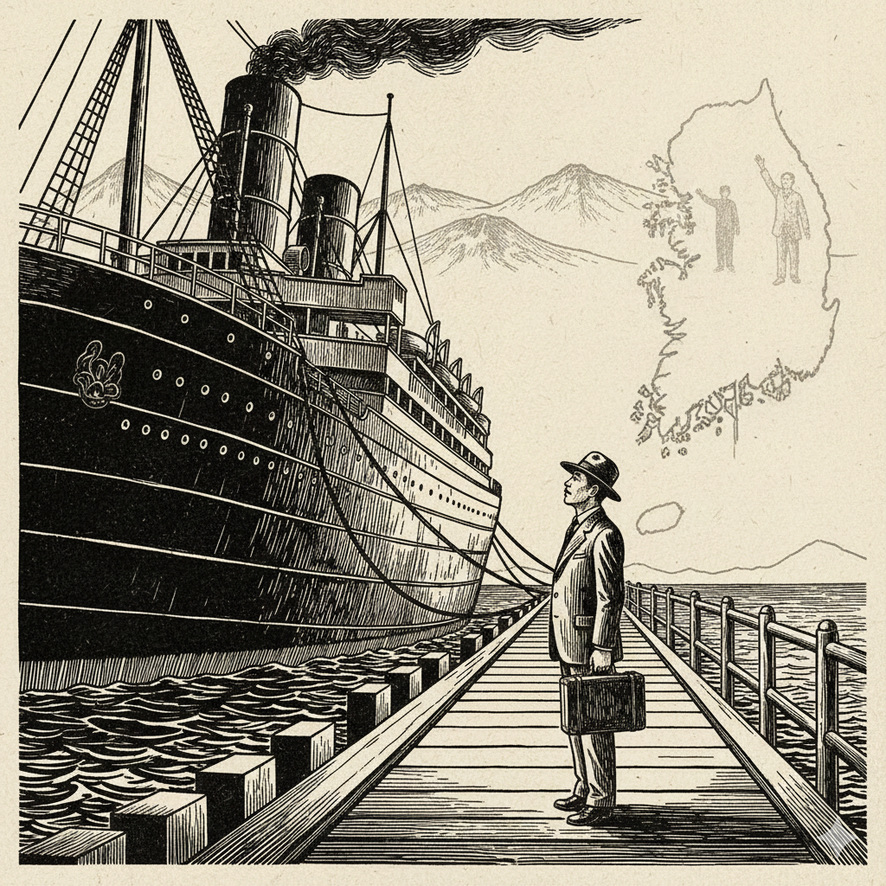

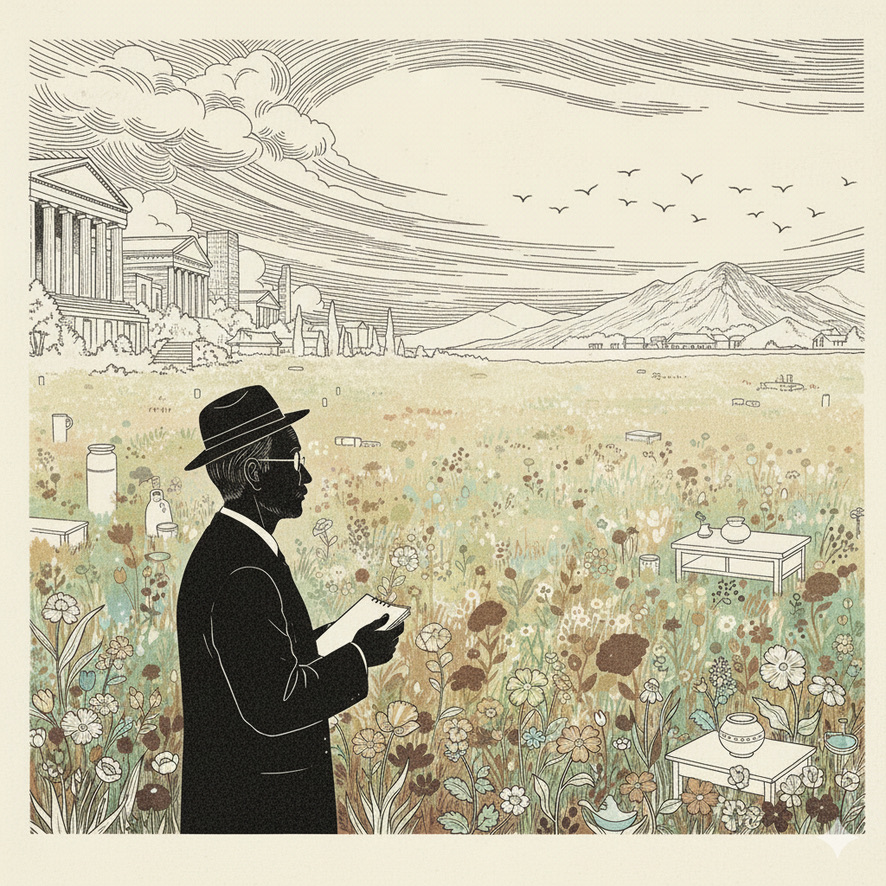

從朝鮮十年(1914-1924)到民藝十年(1926-1936),20多年的歲月,柳宗悅從24歲的青年到47歲的壯年,從徬徨到頑固,從猶豫到堅定,從青澀到成熟。他已不再是早年那位熱衷宗教哲學的白樺派知識人,而是民藝運動的核心組織者與論述者。1936 年前後,「他力道」、「用即美」不只論述定型,柳宗悅在《工藝》發表了許多重要論文,而觀念也開始跳出文字、透過博物館、展覽、收藏與網絡在制度化運作。

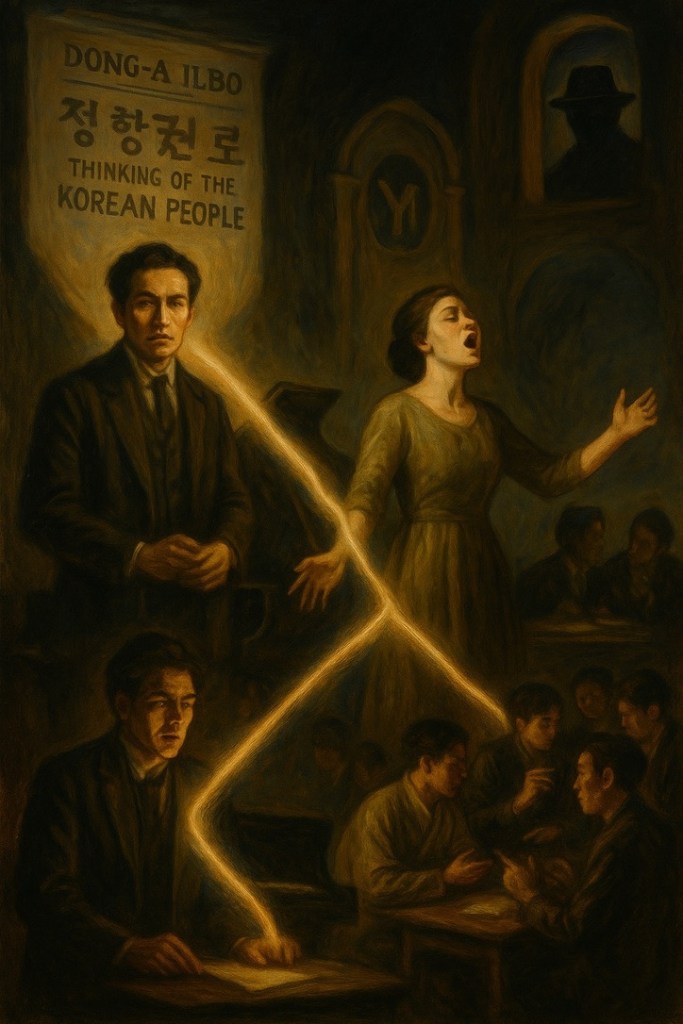

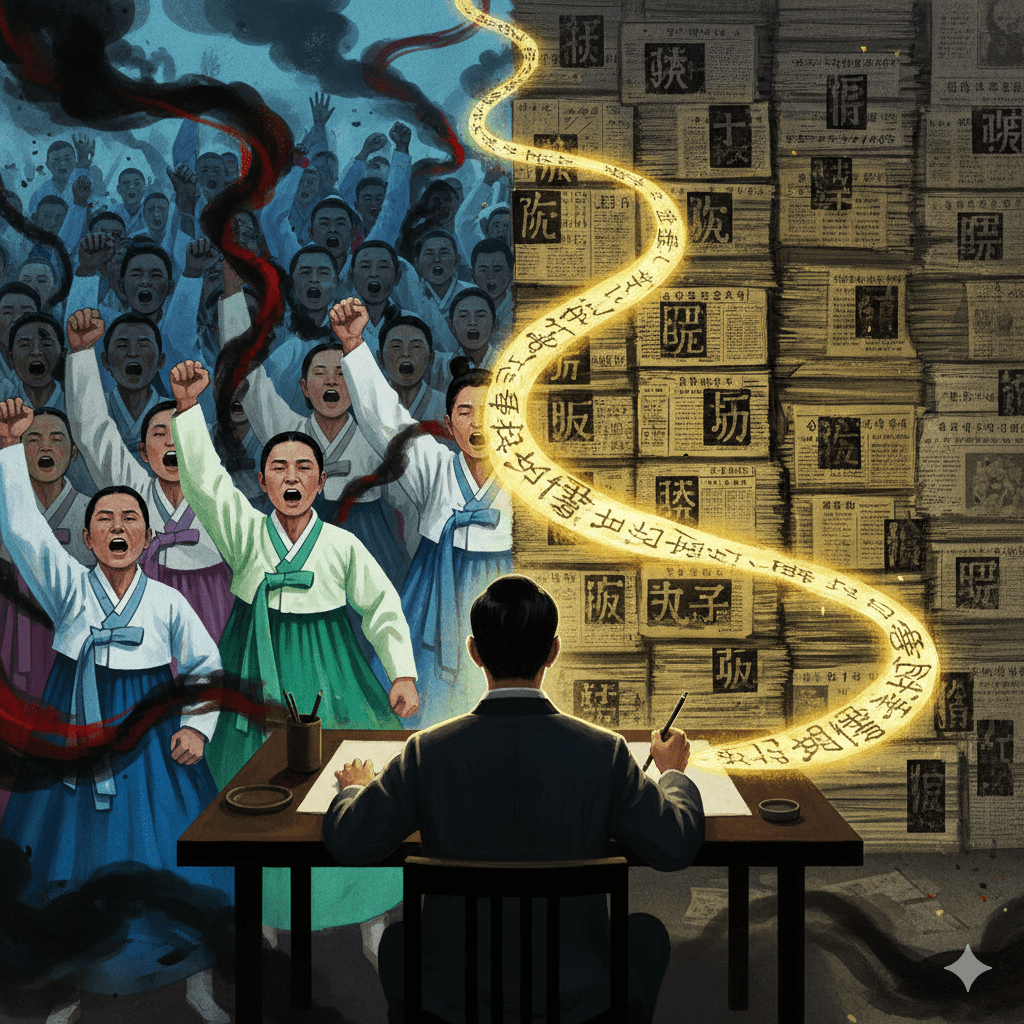

從一人到三人到眾人,從背負創造一個體系的責任到被一整個自己創造的體系所要求,從嚮往鼓吹無名到背負名聲的負擔與期許,柳宗悅已經把「民藝」轉換成了對自己與對參與的成員們都具有彼此約束力的理念與承諾。是的,民藝已經成為了一個雖然參與者分散各地但彼此共鳴協力,抵抗官方工藝體制的運動力場。

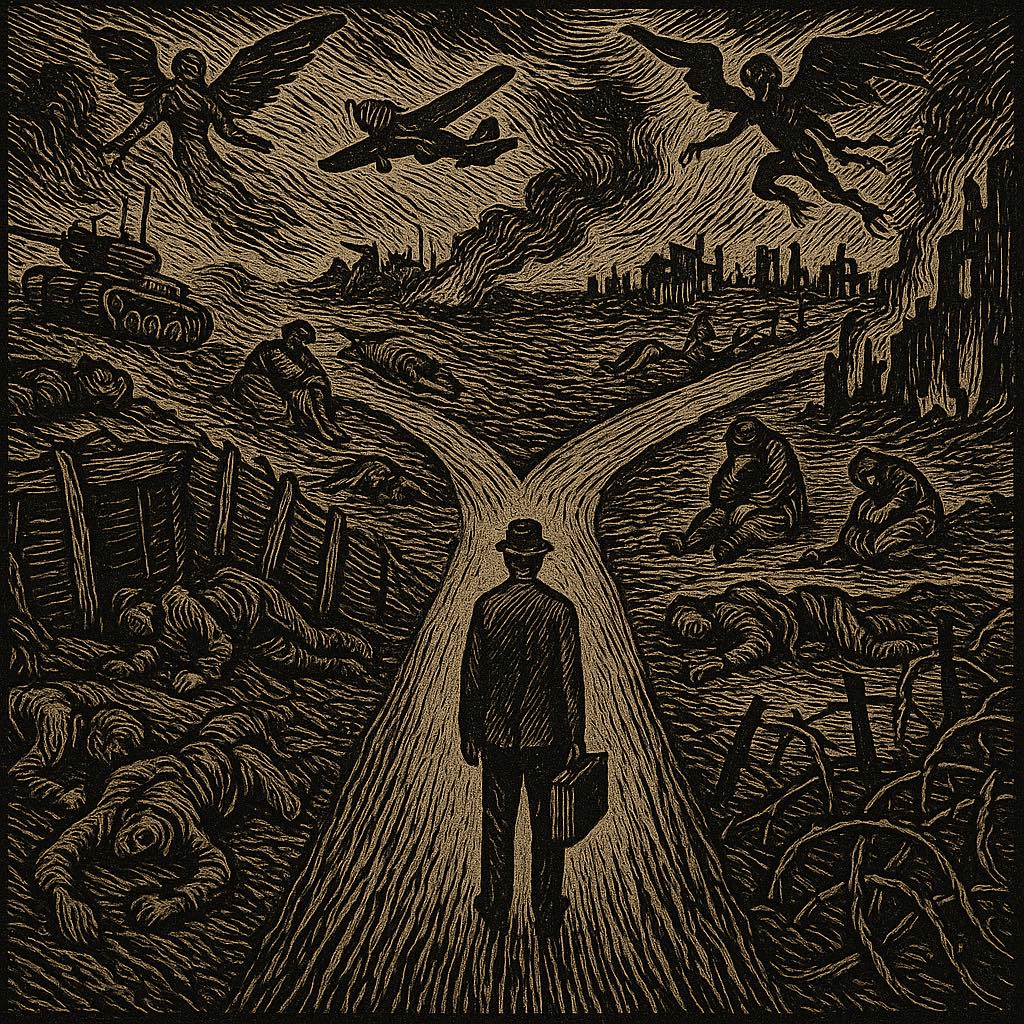

同樣的時期,世界經歷了重大的變化,日本的現代化歷程從大正民主不幸地急速轉向軍國主義的抬頭。

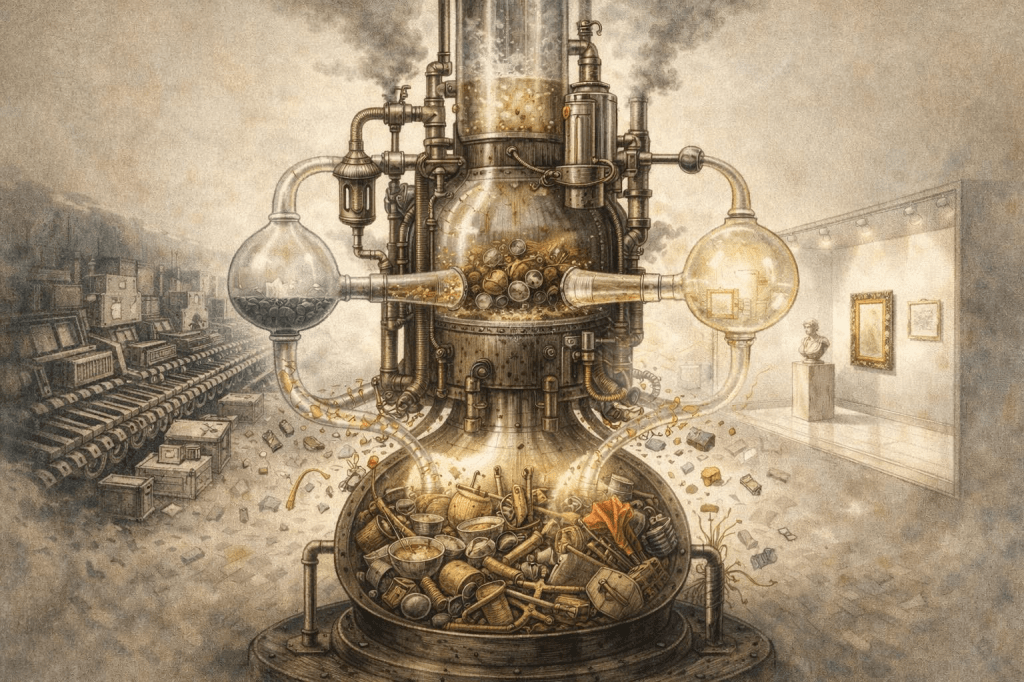

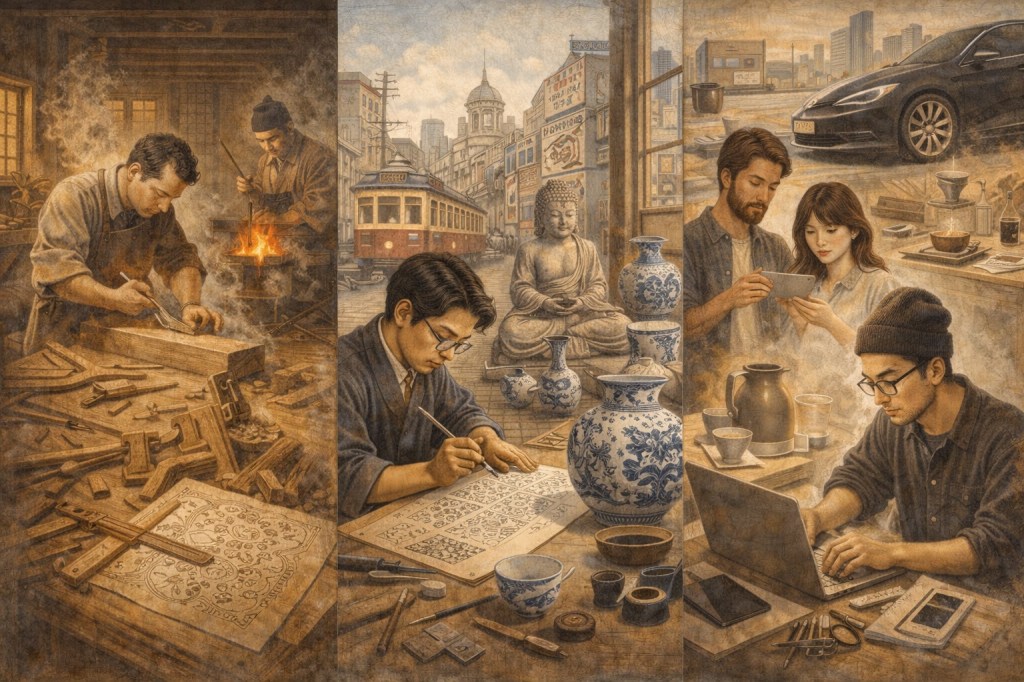

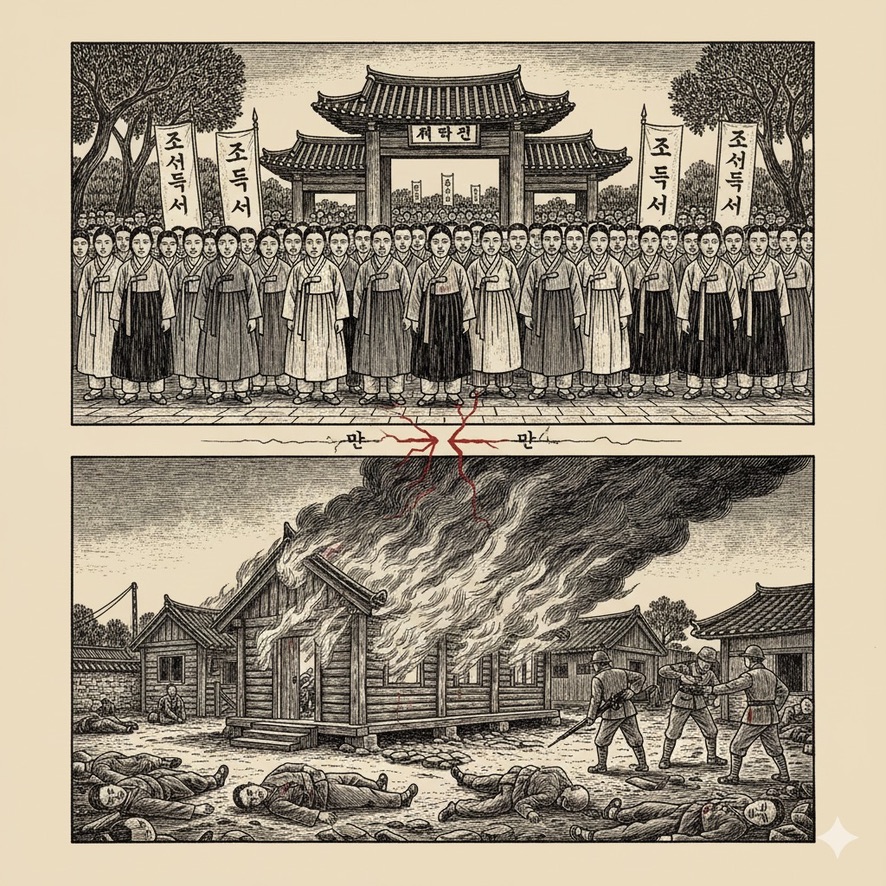

民藝質疑的對面,明治政府的煉金術將日本的命運跟「現代」的主題綑綁套緊在一起。近代化的巨大工程在「殖產興業」與「文明開化」的總目標下轟隆前行,工商發展快速沛然有成,形塑了歐美之外亞非世界極為罕見的成功案例,具體展現在先後打敗中國(1894–1895 年 甲午戰爭)與俄國(1904–1905 年 日俄戰爭),以及取得台灣(1895 年《馬關條約》)與朝鮮(1910 年《日韓合併條約》)兩個海外殖民地的躋身強國之列。

然而,圍繞著「現代」不只榮耀還有社會轉型的巨大苦痛,形諸都市化、工業化、商業化與世俗化等天翻地覆的變遷,逼迫日本人在各自的具體處境中做出攸關生命的抉擇。

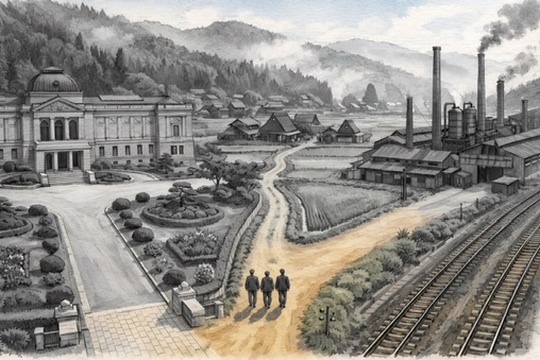

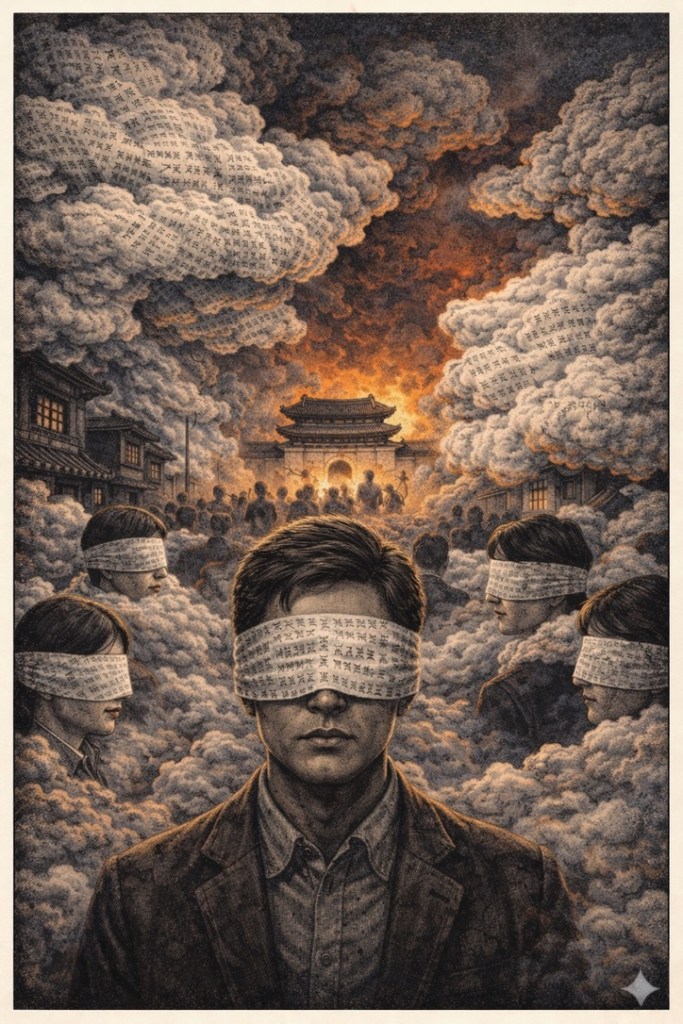

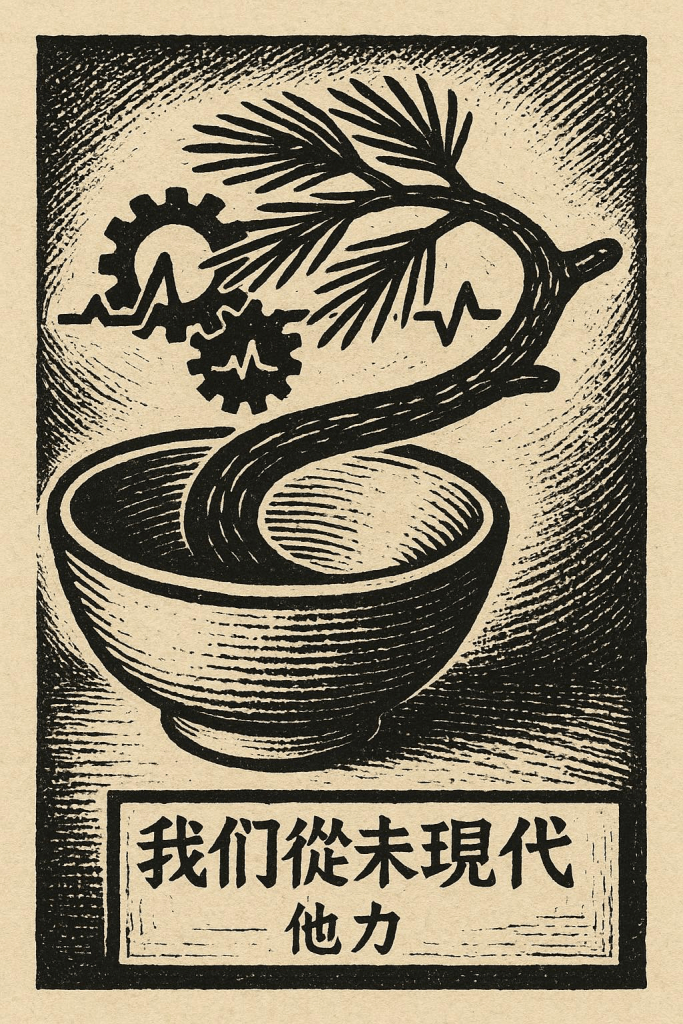

如同民藝運動透過產地與都市之間的連結回應這些衝擊,軍國主義擴張則是日本政府在現代化過程中,扭曲地回應困難挑戰所給出的行動方案:需要團結以便經濟擴張但擴張必然又帶來社會撕裂,在關東大震災後的經濟蕭條衝擊下,痛苦挫敗與驕傲自信雜陳交混,這些矛盾終於迎來了「超克近代」的官方版本,一旦進到國家機器,「超克近代」就不再是反省,而成了統合與擴張的操作語言,結果是:以國粹主義與天皇國體為名,用法西斯式的集體統合對內整合(排除的暴力)、對外擴張(侵略的暴力),克服危機瓶頸,以維持國家資本主義的再生產。

就像「後現代」在我們的時代不只沒有超克現代,事實上還徹底解放了「現代性」裡懷疑一切、徹底分化的虛無幽靈;企圖超克近代的日本並沒有創造世界史的東方新境,最終反而更放肆解鎖了現代性裡暴力潛質的擴散。

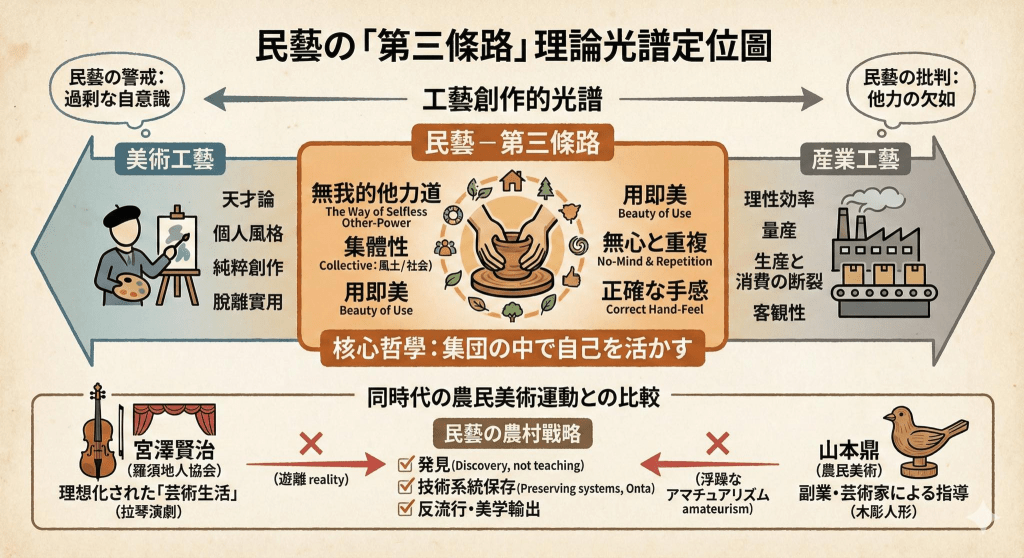

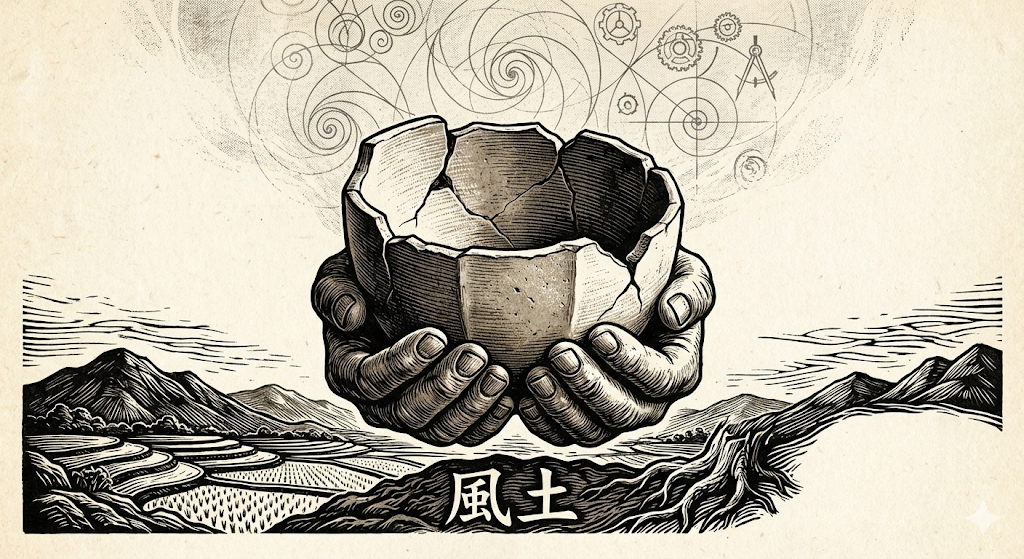

民藝作為對抗明治政府國家主導現代化企劃的一個文化運動,同處在強勢的現代洪流中掙扎求生,主張回返「前現代」是要如何推動時代前進?聲稱事事不離集體,難道不會讓徬徨的現代個體更加沈陷迷途?盯著前現代集體的民藝如何可能迴避日本悲劇性的現代歧途?對比明治政府承諾的恢宏現代藍圖,還能提出怎樣的願景?

這一節我們要來收攏這兩條線,把「民藝」這個對抗性的運動內局部力場,放到「現代」這個更強勢主導時代的力場中,交織沈下貼近場中的個體,來再次檢視「民藝地存活」的意義。

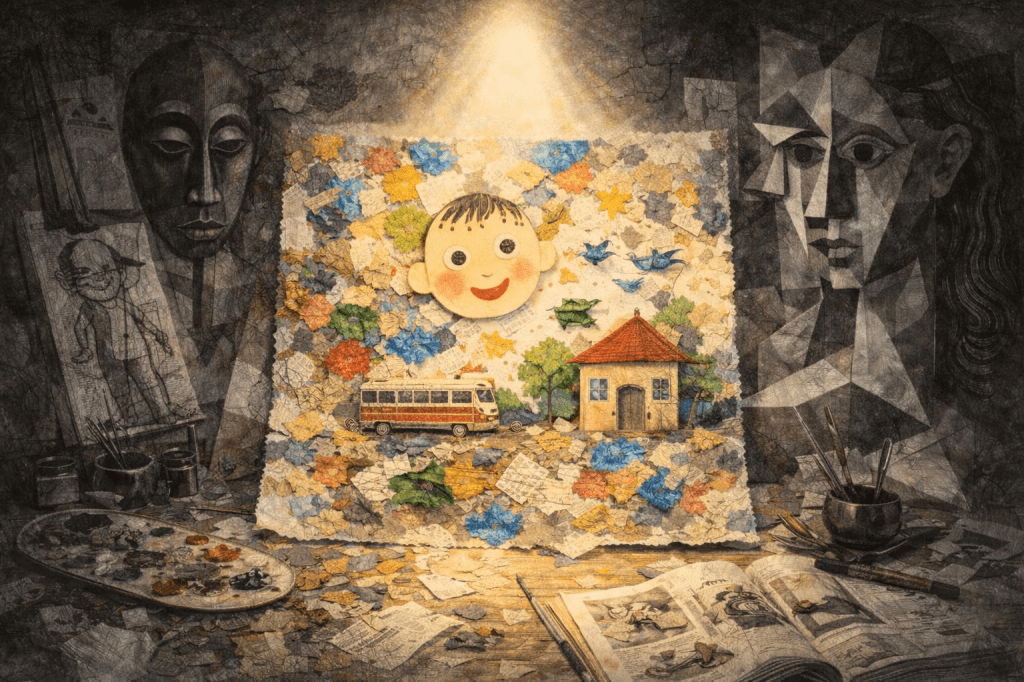

我們在總結第一部「萌芽:思想的種子」的「1-4 神秘的實在」便提及:「分化」是現代性的核心特質。我們現代人直覺理解的「藝術」就是一個分化的獨立領域,而處於這個分化領域核心的「藝術家」更常被視為所謂「現代個體」的鮮明表徵,是英雄主義敏感悲劇地隻身對抗任何集體的美學現身。

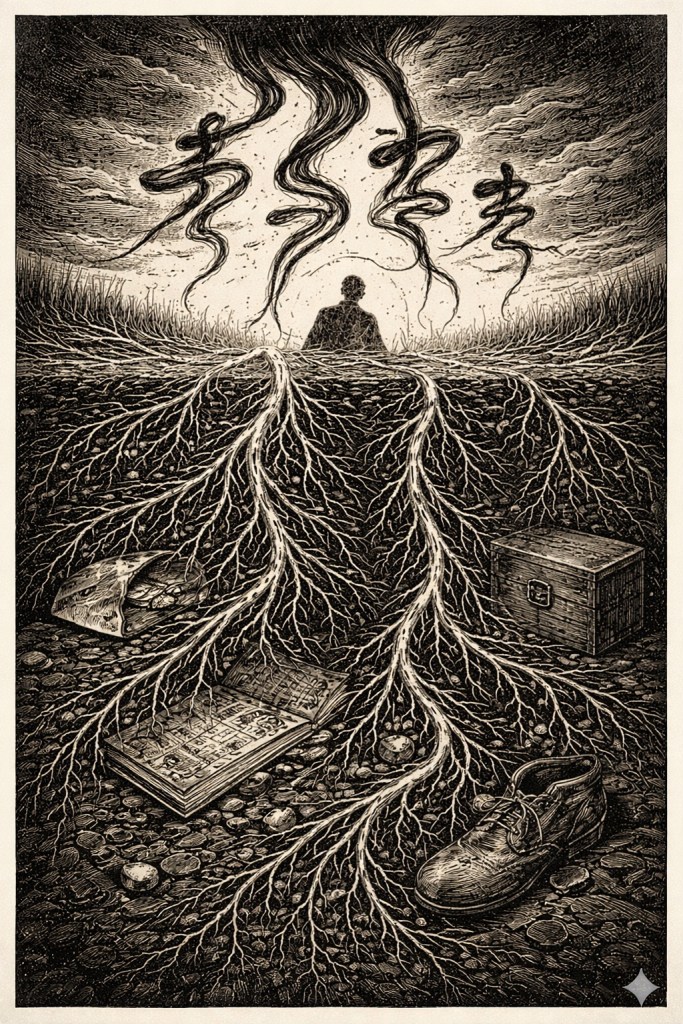

然而,民藝從根本處反對的,正是這種以分化為前提的「藝術」理解,認為它體現了現代人對世界與自我的偏執誤解。現在,跨過三章的篇幅,跟著柳宗悅從青年走到壯年的20多年歲月,看到從一個男孩心底的一顆思想種子,到如今落地生根成為一場眾人協力的文化運動,既然跟著他一起成長,就壯膽些深入制度的人性底層,來具體理解這個稱為「現代」的分化過程,試著看穿之前提及「現代性」的輕重虛實,調準所謂「民藝」遙指的未來方位。

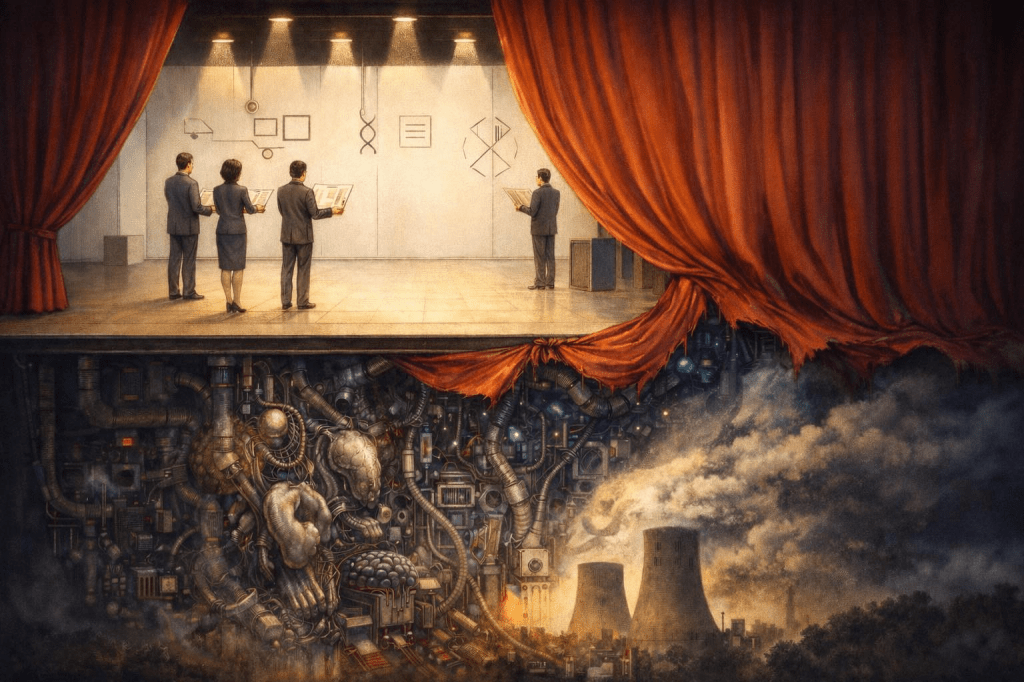

明治政府的現代煉金術是「作為分化的現代」最清楚的見證,以「前現代」混合了各種「雜質」、畢竟與庶民日常生活雜處的手工業做為國家衝刺現代化的起跑線,宛如透過政策開挖物質文化地層深處的原油,以舉國之力提取下手的工藝來進行加值的現代裂解,從中「分化」提煉出現代工業起步的「產業工藝」與現代文明雛形的「美術工藝」。從此兩者涇渭分明,工匠步入現代化各自追求生涯歸宿。

分化之後接著就是產出的大規模「純化」,不只工藝美術這邊要往「純粹藝術」的高峰上進,產業工藝這邊也要不懈追求卓越。這一切拳拳服膺拉圖所說的「現代憲章」根本大法,藝術這邊表現文明開化「人的價值」,藝術家的自我表現貢獻出人主觀創造的純粹性;工業這邊表現製造效率的「物的價值」,在企業理性管理下發揮生產至上的純粹性。兩個分化世界各有競爭的焦慮,但沒有被混雜侵入的意外不安,這是「現代」許諾的基本安全感。

那麼,抵抗這種分化的民藝,如我們上節曾說的,在工藝被分化提煉純粹價值後還有什麼殘渣「剩餘」?對「被純化」後的現代人而言,更棘手難解的問題是:在藝術之前的那個「未分化的藝術」直覺無理、難以想像,究竟是什麼東西?

為柳宗悅首先立傳的實用主義政治學家鶴見俊輔雖然沒有提倡「民藝」,但是他提出了一個饒富趣味的親近概念——「限界藝術」(marginal art)——或許可以給我們啟示。

現代人理解的藝術,首先是「純粹藝術」(pure art)。進入二十世紀,伴隨大眾媒體與民主制度在世界規模中的成立,反而才出現了作為商業產物的「大眾藝術」(popular art)。從我們今日的視角來看,這兩個基本範疇之間已出現愈來愈多樣且充滿活力的混種(hybrids),並為此衍生出更多分化範疇,但這些細分無涉我們此處的關心,就暫且這樣粗分著用。

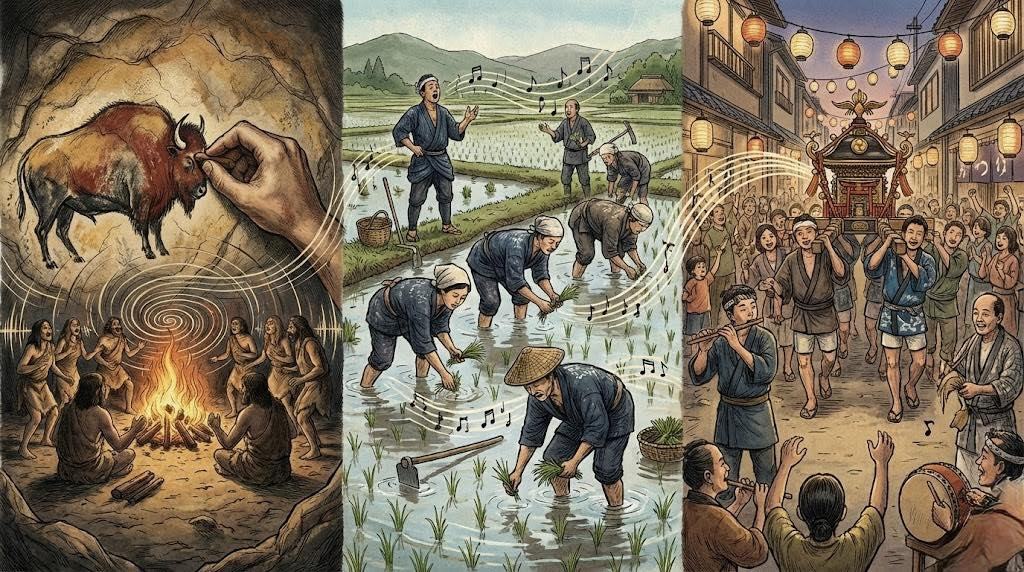

鶴見俊輔指出,相較於「純粹藝術」與「大眾藝術」,還存在於一個更為廣泛的領域:自五千年前西班牙Altamira Cave洞窟壁畫以來,這一類被他稱為「限界藝術」(marginal art)的表現形式,迄今並未出現任何可稱為「進步」的歷史演化。若依今日考古與人類學研究成果回望,這條時間軸甚至可以更大膽地向前推進,延伸至約四萬五千年前印尼蘇拉威西島Leang Tedongnge洞穴中的動物壁畫。這種萬年不變的藝術如今依舊,只是在「現代」之後,近在眼前的它就變得如遠在天邊,被擠到我們意識的邊緣,誰叫它頑固不接受「進步」的丈量。

從生產者與使用者的生態來看,「純粹藝術」由專業藝術家、強調藝術自律的學院或前衛藝術團體、媒介收藏與創造稀珍的藝廊體系所構成。「大眾藝術」(如流行樂與商業電影)保留了專業藝術家,加入製作團隊的專業分工,透過商業化的營利管道,提供給非專業的大眾消費。

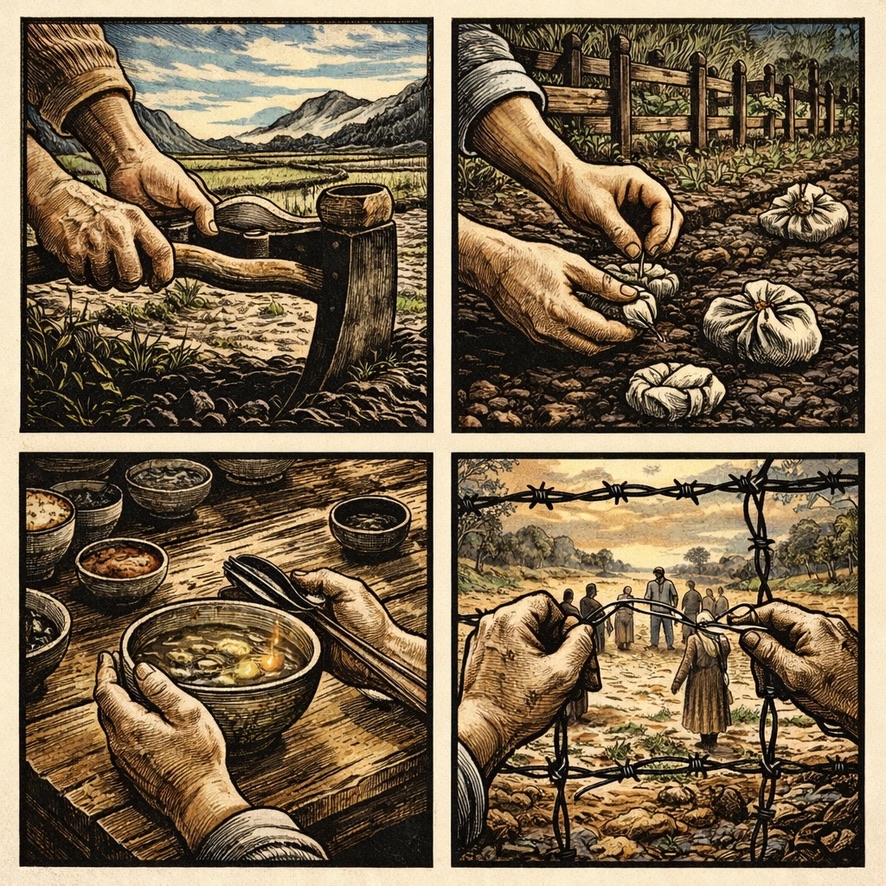

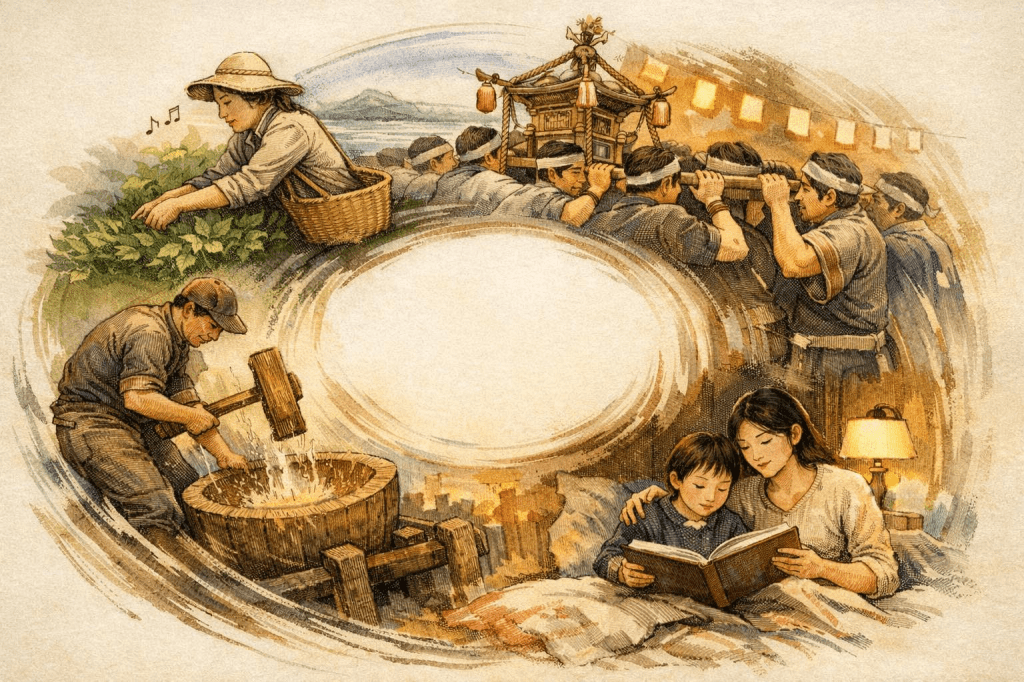

「限界藝術」的特色就在它的不純,是「素人為素人(通常還是自己人)」,發生在民眾日常生活的活動當中,不為回收利益或藝術史留名而作。譬如,民謠或勞動歌,工人、船夫、漁人、茶農、小販……在工作的現場順著工作節奏或勞動情境的觸感而即時吟唱,通常眾人集體參與來回呼應,克服距離,彼此共鳴。

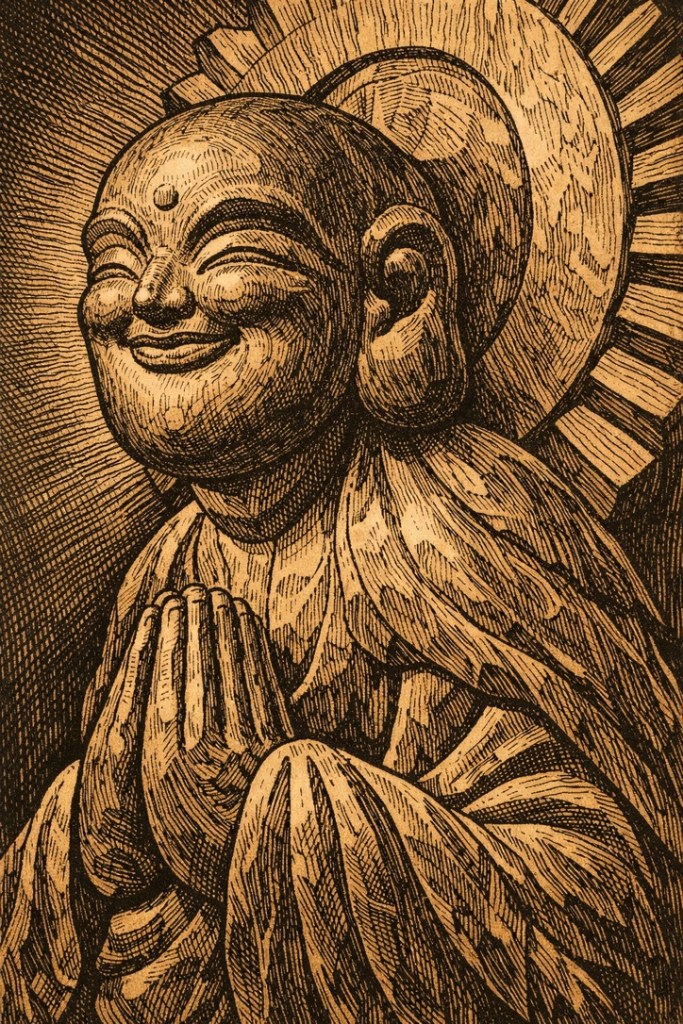

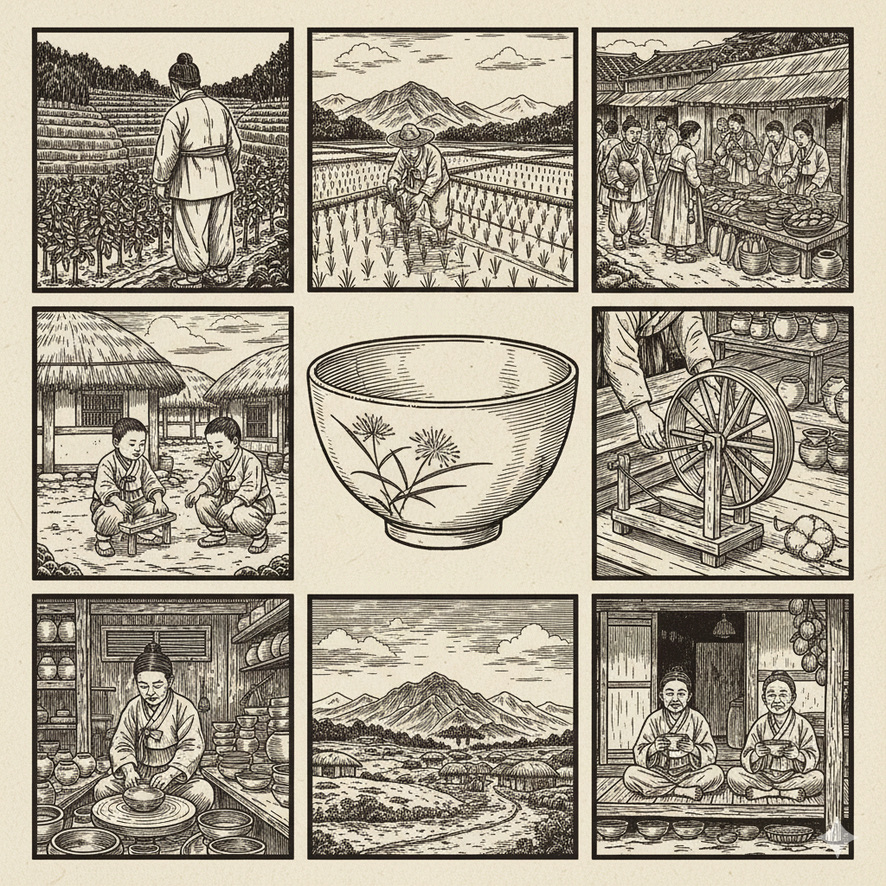

請留意,限界藝術不是工藝,它甚至是手工匠還沒有分化而出前初始狀態的民藝。在手工業的時代,柳宗悅定義民藝為「無名工匠做給無名大眾使用的工藝」,強調「無名」跟限界藝術相同,但不只於此,包括「集體性」、「重複性」與「生活的必要性」也都一致。所以我將「限界藝術」稱之為——從冰河時期印尼洞窟壁畫就開始的——「原始民藝」。

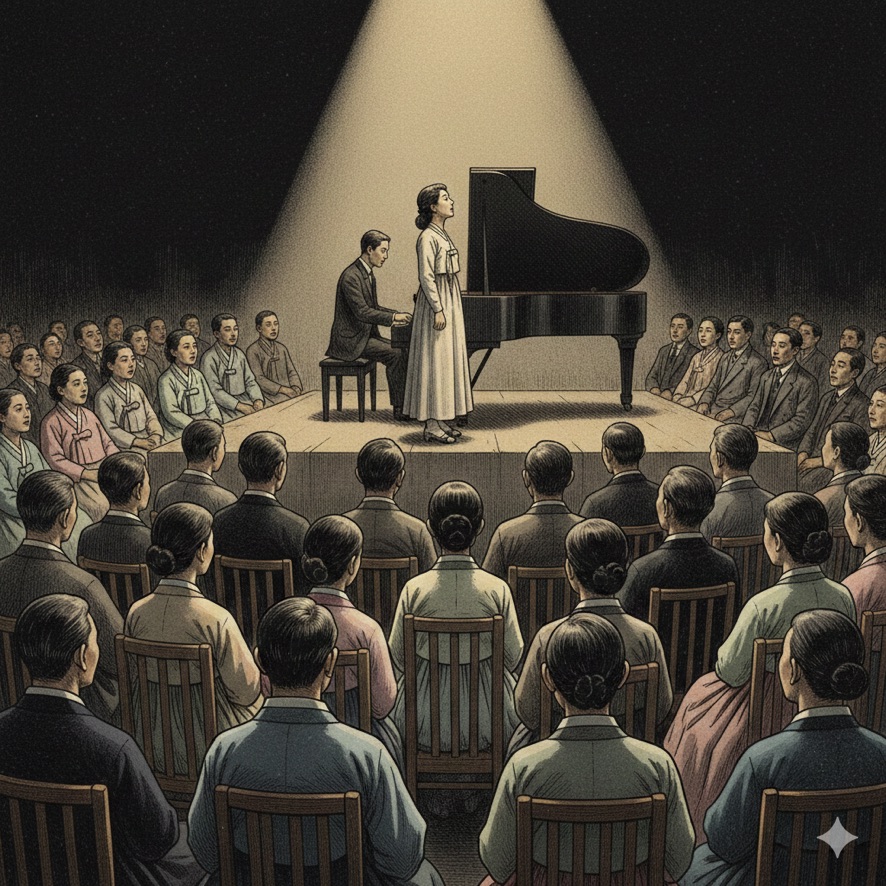

原始民藝跟工匠民藝的差別,在於它是藝術徹底融入生活中的「他力道」與「用即美」。原始民藝經常是沒有觀看者(或旁觀者)的生活形式,柳田國男特別強調這點,譬如,他認為民謠在昭和初期隨著媒體通路出現而從限界藝術轉化為大眾藝術,出現了模擬民謠、擬似作者的流行民謠;然而真正意義的民謠是沒有作者的集體自娛,歌者與聽者可以一搭一唱交替,齊唱互娛才是融入勞動/休閒生活節奏的主題;今日雖然有「為勞動者」而作而唱的歌,提供勞動之餘的大眾娛樂,但勞動過程本身已經變得不可能伴隨歌聲。

更有意思的是柳田對祭典的看法,原本祭典是國民高尚的生活消費,生產活動正是因為祭典的存在而免於單純物質營生的墮落,若僅是聯繫至一個收益中心,就會產生許多名存實亡的腐敗問題。大正昭和時期傳統祭典的衰退,便是源於參演祭典的人與看熱鬧找娛樂的視聽觀眾分離。就這意義來說,知名的大祭已近乎大秀,唯有地方鄉里住民集體參與的小祭,沒有人是祭典參與者之外以觀光獵奇為樂的「旁觀者」,在柳田國男看來才具有「限界藝術」的功能。鶴見俊輔甚至認為,日本人應該以散佈各地的新小祭來重新打造國民信仰,呼籲讓這事「成為我們的義務!」(鶴見俊輔 1999:37)

從勞動歌到小祭典,應該足夠我們了解,原始民藝是更徹底的未分化,它廣泛滲透進入到人類悠久歷史的許多生活角落。想想看,包括現代家庭裡每晚睡前的親子繪本共讀這種「微儀式」,藝術在此並非從生活中分化出的獨立領域,而是與帶著意義的勞動與帶著信仰的生活共時的繞樑餘韻。

所以說,「原始民藝」並不原始,「限界藝術」並不邊緣,它們之所以普遍卻不再容易可見,是因為在我們這些隨現代性的無盡分化「被純化的現代人」眼中,已經看不到貼近的生活本身,當然更難透過限界藝術凝視遠方的「人們如何在社會中生活」。

民藝運動的本質,是一種向著未分化狀態的「有意識回歸」,是對分化下現代人自我誤解的一番克服,它最困難的挑戰在於:如何「不成為」一個「純化的現代人」。既然「純化」是一種現代神話,那麼我們「用」這個意識形態自我欺騙地積極打造出來,實際上混雜自然與文化的現代世界,如果冒險吞下一顆甦醒的藥丸(是真的危險),或者用拉圖的話語「回到地面」(祝你軟著陸),究竟現實裸露後會是怎樣的光景?

意外地,感謝拉圖的犀利洞察,純化的成果竟然是乍看矛盾,各色混種毫無忌憚、接近放肆的生產與蔓延!拉圖認為,正因為現代人在上方位階的憲章層次堅持「純化」(否認混種的本體論地位),我們才敢在下方不受約束地製造混種(核能、義肢、基因改造、氣候變遷、人工智慧、人造器官……)。畢竟,我們已經被預告「純化」,所以「人」不管如何被自己製造的混種怪物擠壓,已經快無挺直站立的空間,終究還是相信跟「它們」這些「物」的世界分離,沒有混雜,我們只是在操縱沒有靈魂的自然,甭踩煞車儘管放手繼續——我們現代人漂浮在抽象的空中自認積極生活。

想想,如果還有一點原始民藝的性靈,願意多少承認物與人始終糾纏,那麼我們或許會像「前現代人」一樣,每動一棵樹都要考慮會不會驚動鬼神。再想想,這會拖慢進步的速度到多麼恐怖的地步。現代人的「強大」,正是來自這種「一邊製造混種、一邊宣稱沒有混種」的虛偽。一旦徹底否認了混合物(Hybrids)的合法地位,我們就可以獲得一種「魯莽的自由」——在憲章的帷幕後方瘋狂並自然清醒地大規模製造失控的怪物。

回到民藝的歷史,我們在民藝跟著政府「對場作」的運動力場內,不意外地可以觀察到許多不從官方強制預設的二分開始的運動線索:

民藝拒絕固守農村,也不在京都久留,因為生產與消費已經糾纏,地方與都市已經互滲,這是民藝比誰都清醒知道的現代現實。因此——希望你走到現在已經不會直覺矛盾——跟國家交涉角力的同時,不能忘記文化風土的生活自主;堅持經營地方必須自立的同時,不能跟遠方的都市斷絕連結;在自由創造中摸索民藝的未來時,更需要積極地全面擁抱他力。矛盾、矛盾、太多矛盾……誰叫你們拆掉現代分化的藩籬成了混種。

踏入民藝的力場,這是什麼狀態?我的回答:保持留在野境,活著,在未分的不安中,然後——如果夠幸運——捕捉一隻屬於你的活獸。

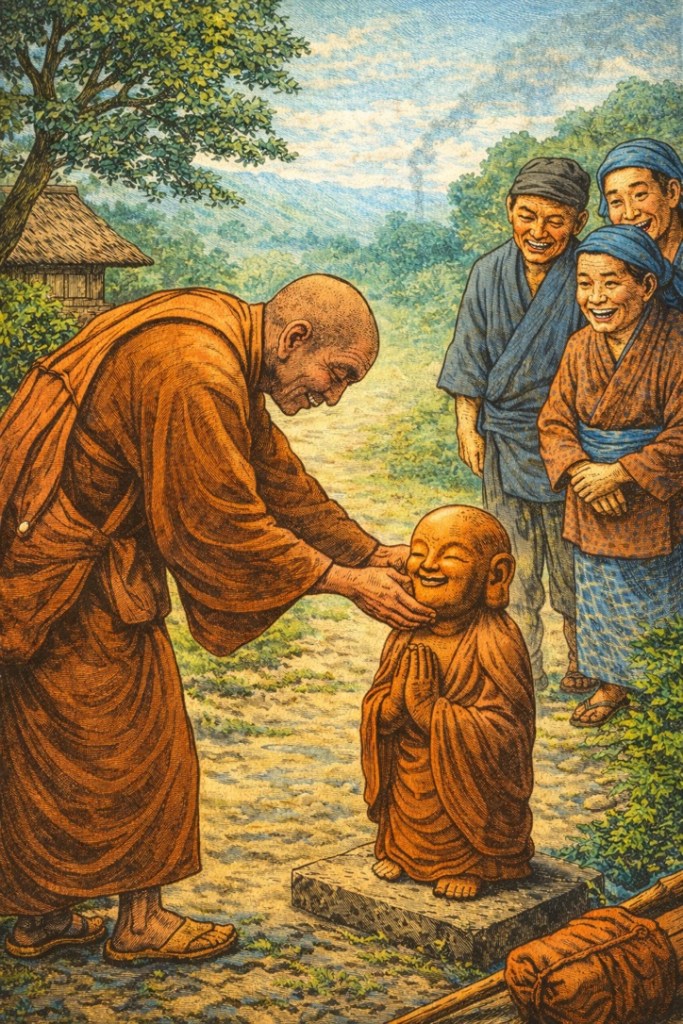

柳宗悅奔走日本各地,1931年,他在九州山裡遇著小鹿田,彷彿看到木喰上人時代的「前現代」活化石生猛依舊,一隻正在眼前咆哮的活獸,想像他那一刻的興奮。小鹿田頑強地抵抗純化,抵抗分化,柳宗悅發現這個叢林中單純活著便是抵抗的活獸,沒有捕殺,反而給他保護、徹底釋放。

未分的野境裡捕捉活獸,容易嗎?不容易。不只困難,而且危險。因為捕捉活獸之前,你必須先主動踏出「分化的圍籬保護」;想抓到活獸,你必須先讓自己被混種的世界抓到。先習慣待在叢林裡,他力包圍的叢林因為開放,所以偶然、意外、不安、所有的失控都是可能,而這些所有你知道不知道的力量,構成了你。生存之道,你必須先接受自己的混種,活到無我不分內外的臨界,「我,是我,跟我的處境」,拿起工具在世界中斡旋生死才能完整自己。然後,你人在叢林,這才準備好了捕捉活獸。

用小鹿田的水車、窯與臼、匠人與陶瓷來跟遠離鄉里,因此自認更現代的都市人談原始民藝與未分的野境,不是一件容易的事,更何況柳宗悅脫口便滿是「無我」、「直觀」、「誠實」的拗口訓示。式場隆三郎身為《工藝》雜誌的主編與民藝運動的總幹事,同時也是一位極為專業的精神科醫師,透過梵谷與山下清進行過精彩的轉譯,讓我們可以一窺民藝未分野境裡的創作臨界。

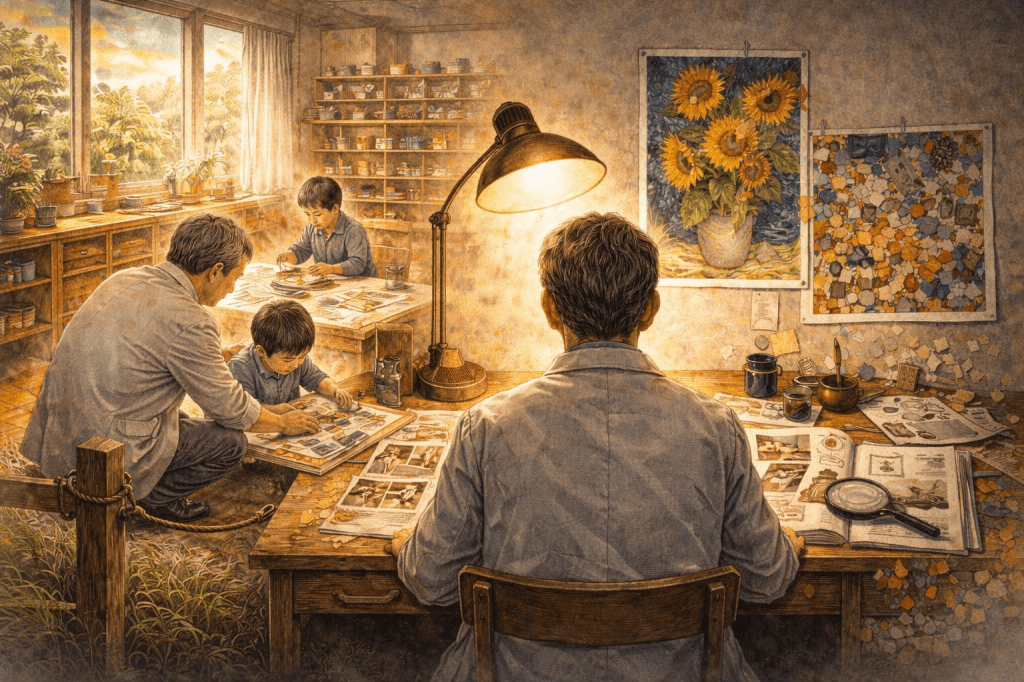

式場隆三郎在民藝館成立的前夕1935年正式加入編輯與營運團隊,次年民藝館成立,他在千葉縣市川市的式場醫院也跟著開幕。他精力充沛地過著上午處理院務與臨床診斷,下午或晚上則投入《工藝》雜誌編輯的斜槓生活,最能看出他如何聯繫貫通這兩個身分的,是他關於梵谷與山下清的藝術醫療/民藝評論。

早在1932 年,式場隆三郎就因為出版《梵谷的生涯》(ゴッホの生涯)在當時的民藝圈引起轟動。柳宗悅在千葉白樺時期就將梵谷與布雷克並列,閱讀這本書喜出望外。式場認為梵谷在比利時波里納日(Borinage)礦區擔任義務傳教士時為了貼近礦工,捐出所有的財物,睡稻草堆弄得滿身煤灰,這種「與勞動者同在」的決心,奠定了他一生藝術的基調。梵谷是從關注底層勞動者開啟他的畫家之眼,他的早期畫作譬如《食薯者》不用畫筆美化農民,而在表現用挖土的手吃土裡長出來的東西,帶著「培根煙燻與薯味」的真實。

晚年的梵谷展現出一種宗教式的狂熱與禁慾的自我消融,式場觀察梵谷「星空」與「向日葵」等畫作,認為進入了比自我意識更寬闊開放的意識流動,色彩與筆觸來自無心忘我,不在描寫風景,更像跟著宇宙律動的宗教儀式。在我看來,式場這番創作狀態的描述就精神醫療範圍是合宜的,但就梵谷的風格評價來看只能說是「創造性的誤讀」,確實成功地讓崇尚西方現代藝術的都市知識分子開始願意接受民藝「直觀」、「無我」的諸多語彙。

實際上,梵谷對西方繪畫傳統中的透視與色彩運用有深刻的鑽研,並非只是直覺而原始,他力感官爆炸飽滿的身體滲入終究導致了瘋狂自毀,或許我們可以說,梵谷捕捉活獸同時也悲劇性地被活獸所吞噬?

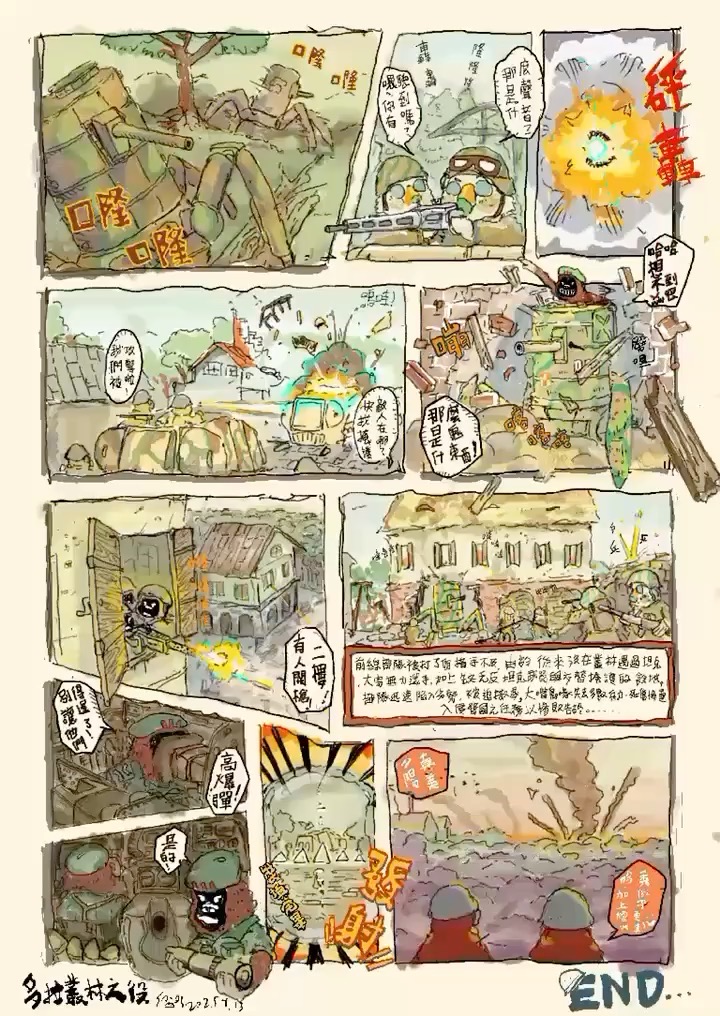

相較於梵谷,式場對山下清這位天才畫家的挖掘與評價,確實給了他力道的創作臨界一個連結民藝遠為有力的詮釋,也是民藝運動意外破格鮮明的一章。山下清(1922-1971)出生於東京淺草。3 歲時因一場重病造成神經系統受損,留下智力障礙與輕微的語言障礙。12 歲時,他被送進千葉縣本八幡的智能障礙收容機構「八幡學園」。學園開啟了他的藝術生命,他著迷於將色紙撕碎後貼在紙上作畫。

1937 年左右,式場作為精神科醫生從診所就近前往固定輔導的八幡學園,驚訝地發現這位素人藝術家構圖與色彩都極其璀璨豔麗的創作力。山下清後來多次逃離學園,長達十餘年在全日本各地流浪。他從不在現場作畫,而是將所有風景刻在腦中,回到學園後再以驚人的準確度拼貼出來。式場在直到1939 年的《工藝》雜誌第 102 號才準備好推出「山下清貼畫」特輯,也發表了〈關於山下清的貼畫〉(山下清の貼繪について)介紹他的作品。

式場在文中強調,山下清的作品無師自通,非來自「構圖」或「色彩學」的教育知見,而是一種原生、純粹的知覺反應。他使用了「非知性的感動」或「原始衝動」來描述這種感官體驗。式場極力主張,大眾不應帶著「同情殘疾人」的濾鏡去看待山下清,因為山下清在藝術上的成就完全不需要依靠這種道德加分。

在式場看來,當時許多畫家是依靠受過訓練的「知識」在作畫,而山下清是靠「視網膜的真實」在拼貼:「那不是智力上的構成,而是肉體化的直觀爆發」(それは知的な構成ではなく、肉体化された直觀の爆發である)。他將這種不為「藝術」、不為名利的「視覺真理的暴動」納入「無心之美」的民藝框架,同時也扣緊精神專業討論了山下清與「原始藝術」、「素人藝術」與「兒童藝術」的關聯。從山下清的作品裡,式場認為,我們看到了現代美術中失去的東西,一種「非知性」的純粹感動,色彩與形狀以鮮活原始的生命力滿溢而出。

柳宗悅不只允許整期《工藝》被一位素人藝術家的主題佔滿,還配合在民藝館裡為這位當代素人畫家策展,他親自為展覽背書,認為少年的作品具備了「民藝」最核心的特質:不帶虛榮的誠實。在雜誌刊載的對談中,他說,這種美不是來自於「自我表現」(Ego),而是來自於一種近乎本能的、對萬物的愛。他作畫時不求美,而美自然降臨。山下清從不在流浪之際作畫,回到學園後才專心一意把記憶裡的景色用貼紙紀錄下來。他流浪之際穿著簡陋破爛自以為樂,態度大方從容,突然出現回園作畫時心無旁騖,於是在學園裡被笑稱是「裸體將軍」(裸の大将)。

山下清的創作必須重複百千次撕碎細如髮絲的紙片,還要近乎自我折磨的反覆貼合,但他有一種跟小鹿田工匠一般的環境通透與沈穩自在,呈現出重複習慣中的美感。式場,毫不猶豫地稱山下清的貼紙畫為「健康的藝術」,拿來跟當時日本文壇推崇的、充滿病態呻吟的私小說形成鮮明對比。式場是日本病跡學(Pathography)的先驅,他曾留下金句:「藝術是天才的病態,而美是凡人的健康。」他指陳現代藝術過度追求「天才的病態」而顯得扭曲、失去了「生活的健康」,這與柳宗悅嚴肅的民藝訓示讀起來毫無違和。

式場的貢獻在於證明了「無我」與「直觀」不是宗教玄學,而是一種健康的生命能量,讓讀者感受到,民藝並非高高在上的教條,而是連被視為「殘疾」的孩子都能自然流露的「健康的真理」。

把式場的山下清與柳宗悅的小鹿田匠人放在一起,合理嗎?他們都同意看到了一樣的民藝野性在震動。野性,只有放到現代憲章分化的前提下才會成立,但它不過是抽象之下的現實。「我們從未現代」,不意味著我們要「回到前現代」,「未分的野境」過去、現在、未來一直都在。因為不符合現代憲章,所以山下清與小鹿田不容易被現代人理解,更不用談被接受。在飛鉋聲中忘我的工匠與在紙片中塗鴉的山下清都在同一個節奏裡,專注無我,作業重複,開放地活在環境裡成為環境。

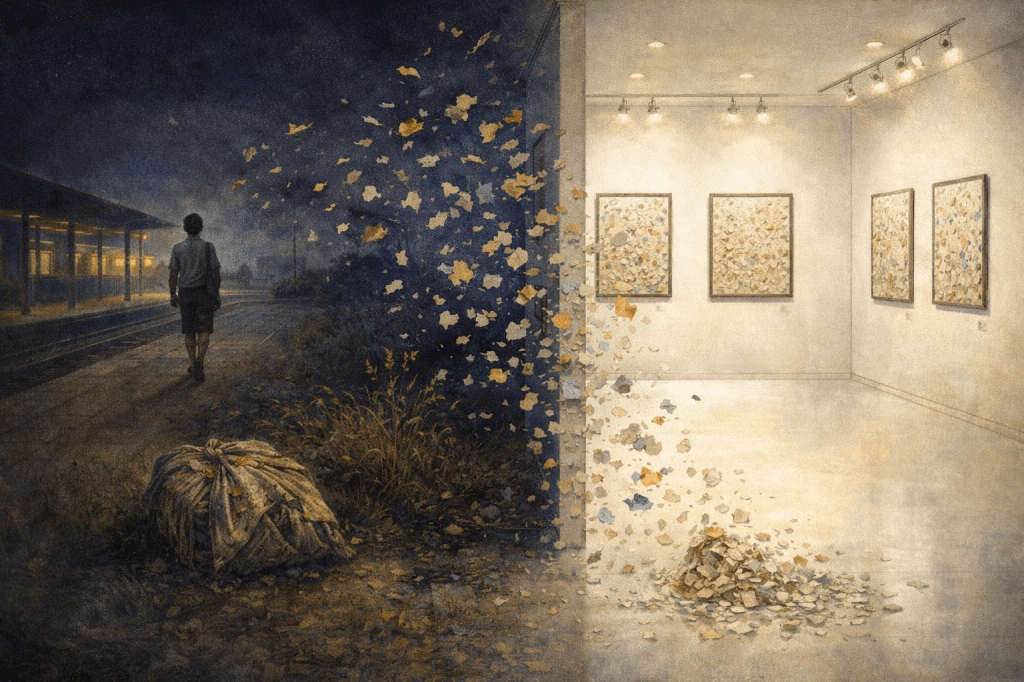

對式場而言,如果把山下清從他的「流浪脈絡」中抽離,放進乾淨的藝廊打光,那就是在獵捕一隻早就坐囚的死獸。對柳宗悅而言,參觀者將一件小鹿田燒如化石般孤立出來欣賞,那頭產地的活獸便面臨滅絕的威脅。山下清不時流浪,小鹿田堅持不動,沈澱生活的力量一樣,兩者的差別卻也勾勒出了民藝未分野境的寬幅力場。

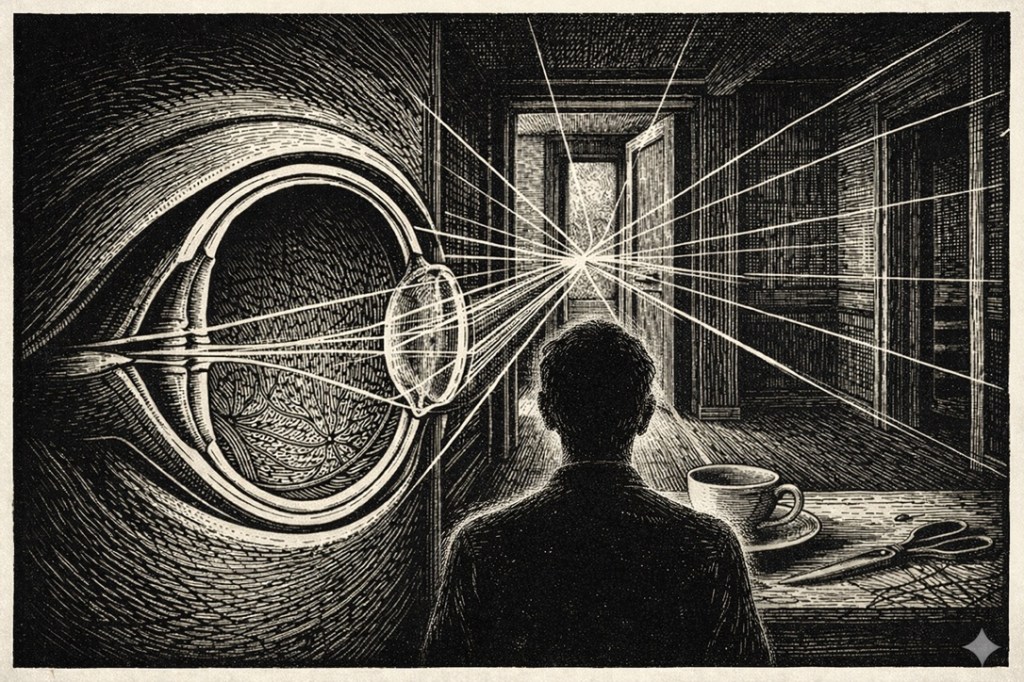

奧特嘉(José Ortega y Gasset)所說的那種「忘我的專注」——像原始人類在森林中討生活那樣,為了生存必要將自我消融在環境的直觀裡,讓我們很自然地容易理解他另外那句如同咒語般的提醒:「哲學的工作,是在叢林中獵捕活生生的獸。」作為現代性的處方箋,民藝品那種「厚重、實用、有脈絡」的特徵,正是為了喚醒我們,重新與即便現代那未分野境仍在的現實掛鉤。但這極其困難,因為分化是一門好生意,熱心產業或者熱心藝術的,都懂。

普列希特(Richard David Precht)的《西洋哲學史》第四冊「人造世界」,用畢卡索的「亞維農的少女」立體派畫作為1920s後的哲學新世紀開幕。被如何突破找到自己獨特創作個性搞到快發瘋的畢卡索,在1906年造訪特卡德羅民族學博物館時看到非洲原始藝術的面具,畢卡索感到「噁心」跟著找到突破的切口;這噁心,或許是文明人與原始力量碰撞後的本能排斥與強烈著迷。相較之下,山下清與小鹿田匠人本身就棲居在叢林裡。民藝的野性不是被提煉出來的風格,而是與泥土、節奏、勞動糾纏在一起的、未被純化的現實。

野性與原始迷人,被天才藝術家機敏地拿來加工純化以堆疊個性,「亞維儂的少女」(The Young Ladies of Avignon)巨幅畫面上破碎、分裂、不忍卒睹、沒有任何一體的線索,甚至讓人感到厭惡。但他最終成功,1925年「亞維儂的少女」被購買後刊登在《超現實主義革命》雜誌上,從此「立體派幾乎改變歷史,而激進的前衛主義也成了大家的口頭禪」。似曾相識?我們再度回到「布雷克的T字路口」(見1-3 自動書寫),這次你選擇右轉還是左轉?

奧特嘉同年出版了《藝術的去人性化》(The Dehumanization of Art),他用「去人性化」標識這場前衛藝術的革命,用意不在批判,只是中肯地指出了新興的藝術家在玩的把戲,甚至帶點菁英主義的欣賞:超現實主義的藝術領袖們不再祈求觀眾的情緒共感,他們壓根就不想被喜歡,決心要讓藝術更徹底分化「回歸到藝術本身」,他們刻意激怒看不懂的觀眾,讓他們感到被羞辱進而排斥。這種故弄玄虛效果卓然,篩選出了「真正在行的審美者」,並給予他們敏感現代脈動並富於反身批判的思辨地位。在《大眾的反叛》(The Revolt of the Masses)裡,奧特嘉甚至認為,前衛藝術用分化的藝術製造出了菁英與大眾間的「社會分級」效果。

然而,奧特嘉同時也預見了挑釁的邊際報酬遞減:大量複製的套路,諷刺、遊戲、幻象……號稱為了刺激大眾推測思辨,其實把自己更深地關進美術館,當形式耗盡便宿命地只能陷入淘空,不只疏離了大眾,而且造成了即便審美菁英們也難免的批判神經疲乏。

普列希特用悠遠的回顧語調這麼評論:

「他的《亞維農的少女》所召喚的鉅變本身成了藝術生產的文化『規範』。正如奧特嘉所說的,從現在起,它承擔了一個巨大的現代性壓力,這個壓力持續了整整一個世紀:藝術是以形式的創新在挑釁社會。直到種種形式的可能性都被淘盡了——而他同時也喪失了社會性的意義。」

奧特嘉在《什麼是哲學》中要我們煞車回到生活,生命就是「我與我的處境」的交織,而當代人最悲劇的沉淪就是躲進了各種「分化」的保護殼裡,忘記了生命本質上是一場「向著未知的航行」,我們該回到原始獵人「全感張開」(Pan-attention)無我地投入處境的本真,如在現實的叢林中捕捉活獸,用對世界的開放,活出那種具備冒險精神的存有。

民藝的第三條路,是主動撤除「現代憲章」保護下的虛假圍籬,回到那個物我糾纏、充滿偶然與驚異的未分野境。在那裡,你捕捉到的不再是一件供人賞玩、被去人性化的「藝術品」,而是一次驚心動魄的「存有相遇」。這頭活獸,可能是那只在飛鉋聲中現身的小鹿田燒,可能是碎紙片裡爆發的視覺真理,也可能是那個在無盡分化的現代性壓力下,重新找回生存體感的、最真實的你自己。那是神祕實在裡,唯一能證明你正與世界同在、而非漂浮在抽象空中的座標。